In every room I’ve ever walked into, from the lab to the hospital floor, within seconds I’ve found someone who seems to have it more figured out. Someone whose pipette technique is cleaner, whose résumé is longer. For years, I thought the only way to belong was to become them – or at least something like them.

There’s an old quote, attributed to President Theodore Roosevelt, that says “comparison is the thief of joy.” It sounds simple, like advice you’d find on a placard in a Midwestern kitchen, but for those who live inside competitive worlds, it cuts deep. Because comparison isn’t just a passing thought; it’s built into the system.

It’s the curve on every exam, the list of research grants, the conference acceptance email that makes your heart jump – especially when it’s not yours.

The Myth of Enough

Comparison thrives on the illusion of linear progress, the idea that everyone’s on the same path, moving at the same pace and that someone else’s “ahead” means you’re “behind.”

Octavia Butler’s “Parable of the Sower” (1993) wrestles with this illusion too. In a collapsing world, the main character Lauren Olamina doesn’t chase perfection. Instead, she builds community from uncertainty. Her strength lies not in mastery, but in adaptability, in accepting that growth is nonlinear and survival often means rewriting the rules.

In science, that illusion is especially cruel. You measure your worth in outputs: data, papers and presentations. In creative spaces, it’s equally sneaky – likes, shares and publication counts. The truth is, though, you only ever see the finished, seemingly perfected version of someone else’s story.

You don’t see the late nights, the rejections and the doubts that look a lot like yours. You don’t see the compromises they made to get there.

According to verywellmind, a mental health platform, the human mind is terrible at finding perspective; we measure our insides against other people’s outsides and call it reality.

Susanna Clarke’s “Piranesi (2020)” lives inside that tension, the feeling of being trapped in an endless house of achievements, each hall more intricate than the last. Yet, the narrator finds beauty in the stillness, in the act of noticing himself.

When I finally admitted that I was tired, not from the work itself, but from the constant measuring, I realized that comparison wasn’t motivating me anymore. It was paralyzing me. Every accomplishment felt like it expired too quickly. Every joy dissolved the moment I saw someone doing more.

Joy as Resistance

Learning to reclaim joy has been an act of resistance.

Not the loud or defiant kind of joy, but the quiet, everyday kind: choosing to celebrate small things without asking if they “count.” Choosing to write an article because it matters to me, not because it might look good in a portfolio. Choosing to find beauty in the overlap of disciplines instead of apologizing for not fitting neatly into one.

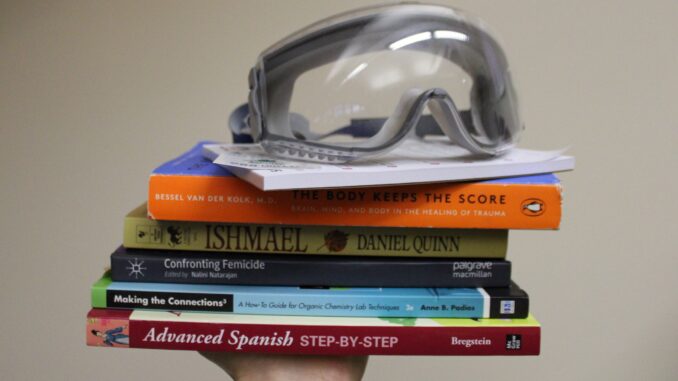

Daniel Quinn’s “Ishmael” (1992) and Margaret Atwood’s “Oryx and Crake” (2003) both hint at this kind of resistance, the act of creating, of caring, of noticing beauty even in a decaying world. To find joy, even fleetingly, in chaos is a radical act.

I’ve started to think that maybe being a “jack of all trades” isn’t a flaw at all. The full phrase, after all, is “a jack of all trades is a master of none, but oftentimes better than a master of one.” It was never meant as an insult; it was a compliment to versatility, to those who could adapt.

The modern world needs more of that. Science needs communicators. Policy needs artists. Journalism needs scientists. Every bridge between fields widens the possibilities of what we can understand.

Finding Joy in the In-Between

Katabasis, the journey into the underworld, appears again and again in literature, from ancient myth to contemporary novels like R.F. Kuang’s aptly named “Katabasis” (2025). Descent isn’t failure; it’s transformation. To go down and return changed is the truest form of mastery.

Maybe being “in-between” disciplines, or not yet “there” isn’t a flaw, but a kind of katabasis too, a necessary journey through uncertainty to emerge with something new.

I’m still learning how to live with that concept. Some days I get it right; other days I hop on LinkedIn and doomscroll.

But I remind myself that no one can steal joy I refuse to give away. That the satisfaction of doing something wholeheartedly is more lasting than the thrill of winning a race I never wanted to run.

Maybe joy isn’t the opposite of ambition. Maybe it’s what happens when ambition remembers to breathe.

So, to anyone else who feels stretched between worlds, who’s always halfway between disciplines, halfway between identities, halfway between confidence and doubt, I hope you know that you’re not behind. You’re just building a wider map.

And somewhere in the middle of all that, joy is still waiting to be found.

Leave a Reply